Exam Details

Exam Code

:SBACExam Name

:Smarter Balanced Assessment ConsortiumCertification

:Test Prep CertificationsVendor

:Test PrepTotal Questions

:224 Q&AsLast Updated

:Apr 14, 2025

Test Prep Test Prep Certifications SBAC Questions & Answers

-

Question 181:

Read the text attached.

Workplace Diversity The twenty-first century workplace features much greater diversity than was common even a couple of generations ago. Individuals who might once have faced employment challenges because of religious beliefs, ability differences, or sexual orientation now regularly join their peers in interview pools and on the job. Each may bring a new outlook and different information to the table; employees can no longer take for granted that their coworkers think the same way they do. This pushes them to question their own assumptions, expand their understanding, and appreciate alternate viewpoints. The result is more creative ideas, approaches, and solutions. Thus, diversity may also enhance corporate decision-making.

Communicating with those who differ from us may require us to make an extra effort and even change our viewpoint, but it leads to better collaboration and more favorable outcomes overall, according to David Rock, director of the Neuro-Leadership Institute in New York City, who says diverse coworkers "challenge their own and others' thinking."2 According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), organizational diversity now includes more than just racial, gender, and religious differences. It also encompasses different thinking styles and personality types, as well as other factors such as physical and cognitive abilities and sexual orientation, all of which influence the way people perceive the world. "Finding the right mix of individuals to work on teams, and creating the conditions in which they can excel, are key business goals for today's leaders, given that collaboration has become a paradigm of the twenty-first century workplace," according to an SHRM article.3

Attracting workers who are not all alike is an important first step in the process of achieving greater diversity. However, managers cannot stop there. Their goals must also encompass inclusion, or the engagement of all employees in the corporate culture. "The far bigger challenge is how people interact with each other once they're on the job," says Howard J. Ross, founder and chief learning officer at Cook Ross, a consulting firm specializing in diversity. "Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance. Diversity is about the ingredients, the mix of people and perspectives. Inclusion is about the container璽he place that allows employees to feel they belong, to feel both accepted and different."4

Workplace diversity is not a new policy idea; its origins date back to at least the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA) or before. Census figures show that women made up less than 29 percent of the civilian workforce when Congress passed Title VII of the CRA prohibiting workplace discrimination. After passage of the law, gender diversity in the workplace expanded significantly. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the percentage of women in the labor force increased from 48 percent in 1977 to a peak of 60 percent in 1999. Over the last five years, the percentage has held relatively steady at 57 percent. Over the past forty years, the total number of women in the labor force has risen from 41 million in 1977 to 71 million in 2017.5 The BLS projects that the number of women in the U.S. labor force will reach 92 million in 2050 (an increase that far outstrips population growth).

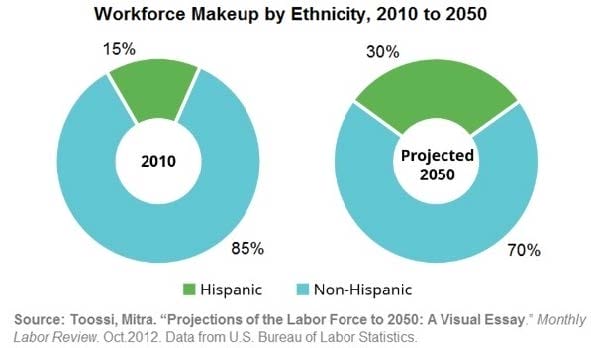

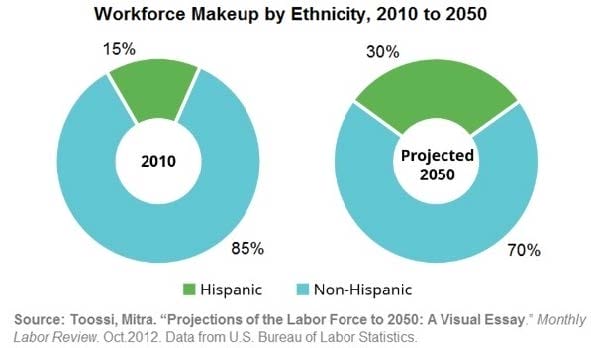

The statistical data show a similar trend for African American, Asian American, and Hispanic workers (Figure 8.2). Just before passage of the CRA in 1964, the percentages of minorities in the official on-the-books workforce were relatively small compared with their representation in the total population. In 1966, Asians accounted for just 0.5 percent of private-sector employment, with Hispanics at 2.5 percent and African Americans at 8.2 percent. 6 However, Hispanic employment numbers have significantly increased since the CRA became law; they are expected to more than double from 15 percent in 2010 to 30 percent of the labor force in 2050. Similarly, Asian Americans are projected to increase their share from 5 to 8 percent between 2010 and 2050.

Figure 8.2

There is a distinct contrast in workforce demographics between 2010 and projected numbers for 2050. (credit: attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license) Much more progress remains to be made, however.

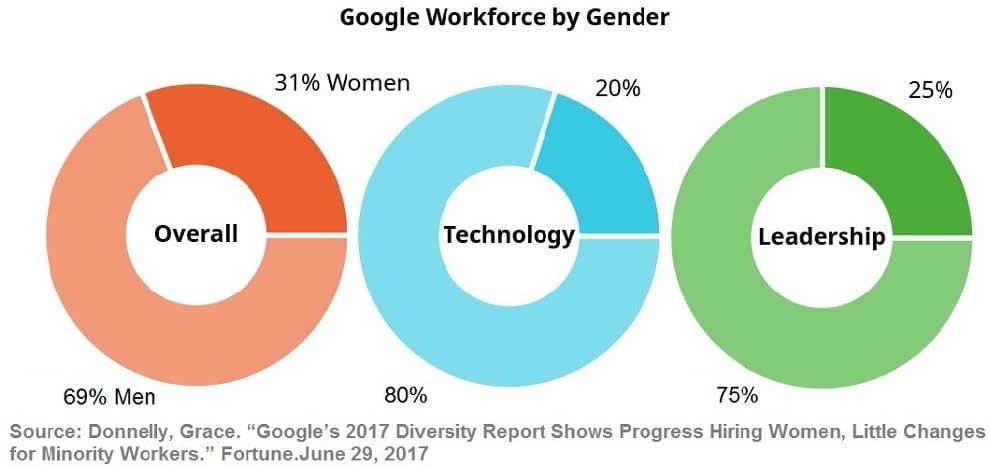

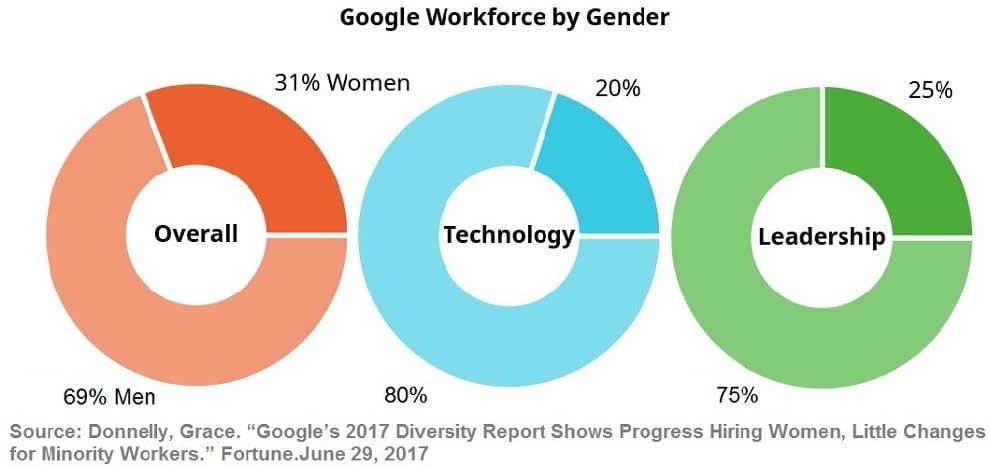

For example, many people think of the technology sector as the workplace of open-minded millennials. Yet Google, as one example of a large and successful company, revealed in its latest diversity statistics that its progress toward a more

inclusive workforce may be steady but it is very slow. Men still account for the great majority of employees at the corporation; only about 30 percent are women, and women fill fewer than 20 percent of Google's technical roles (Figure 8.3).

The company has shown a similar lack of gender diversity in leadership roles, where women hold fewer than 25 percent of positions. Despite modest progress, an ocean-sized gap remains to be narrowed. When it comes to ethnicity,

approximately 56 percent of Google employees are white. About 35 percent are Asian, 3.5 percent are Latino, and 2.4 percent are black, and of the company's management and leadership roles, 68 percent are held by whites.

Figure 8.3

Google is emblematic of the technology sector, and this graphic shows just how far from equality and diversity the industry remains. (credit: attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Google is not alone in coming up short on diversity. Recruiting and hiring a diverse workforce has been a challenge for most major technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, and Yahoo (now owned by Verizon); all have reported

gender and ethnic shortfalls in their workforces.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has made available 2014 data comparing the participation of women and minorities in the high-technology sector with their participation in U.S. private-sector employment overall, and

the results show the technology sector still lags.8 Compared with all private-sector industries, the high-technology industry employs a larger share of whites (68.5%), Asian Americans (14%), and men (64%), and a smaller share of African

Americans (7.4%), Latinos (8%), and women (36%). Whites also represent a much higher share of those in the executive category (83.3%), whereas other groups hold a significantly lower share, including African Americans (2%), Latinos

(3.1%), and Asian Americans (10.6%). In addition, and perhaps not surprisingly, 80 percent of executives are men and only 20 percent are women. This compares negatively with all other private-sector industries, in which 70 percent of

executives are men and 30 percent women.

Technology companies are generally not trying to hide the problem. Many have been publicly releasing diversity statistics since 2014, and they have been vocal about their intentions to close diversity gaps. More than thirty technology

companies, including Intel, Spotify, Lyft, Airbnb, and Pinterest, each signed a written pledge to increase workforce diversity and inclusion, and Google pledged to spend more than $100 million to address diversity issues.9

Diversity and inclusion are positive steps for business organizations, and despite their sometimes slow pace, the majority are moving in the right direction. Diversity strengthens the company's internal relationships with employees and

improves employee morale, as well as its external relationships with customer groups. Communication, a core value of most successful businesses, becomes more effective with a diverse workforce. Performance improves for multiple

reasons, not the least of which is that acknowledging diversity and respecting differences is the ethical thing to do.

You are asked to identify the central idea of the attached passage and use evidence from the text to support your inference. Which of these answers would best accomplish this?

A. The central idea of this passage is that, while diversity and inclusion may be the current buzzwords, companies should be careful moving forward in trying to implement these ideas because the transition can be difficult and stressful and not everyone will embrace the transition easily. This is proven when the text says, "Communicating with those who differ from us may require us to make an extra effort and even change our viewpoint..."

B. The central idea of this passage is that change is slow, and that includes the change in mindset of companies when it comes to hiring. Although the traditional approach has been to hire males, more females are finding their way into the workforce, though more work needs to be done. This is proven when the text says, "In addition, and perhaps not surprisingly, 80 percent of executives are men and only 20 percent are women."

C. The central idea of this passage is to remind people that diversity and inclusion in the workplace not only increases a company's productivity and enhances the morale of the business, but it is the right thing to do to hire the best people for the job, regardless of race, gender, religious beliefs, differences in ability, or any of the other number of reasons people may be overlooked for a job. This is proven when the text says, "Diversity and inclusion are positive steps for business organization, and despite their sometimes slow pace, the majority are moving in the right direction."

D. The central idea of this passage is that not enough is being done to have true inclusion and diversity in the technology sector of society and that many technology companies, including Google, Facebook, and Apple are failing miserably in "leveling the playing field" and encouraging diversity within their companies. This is proven when the text says, "Much more progress remains to be made, however."

-

Question 182:

Read the text attached.

Workplace Diversity The twenty-first century workplace features much greater diversity than was common even a couple of generations ago. Individuals who might once have faced employment challenges because of religious beliefs, ability differences, or sexual orientation now regularly join their peers in interview pools and on the job. Each may bring a new outlook and different information to the table; employees can no longer take for granted that their coworkers think the same way they do. This pushes them to question their own assumptions, expand their understanding, and appreciate alternate viewpoints. The result is more creative ideas, approaches, and solutions. Thus, diversity may also enhance corporate decision-making.

Communicating with those who differ from us may require us to make an extra effort and even change our viewpoint, but it leads to better collaboration and more favorable outcomes overall, according to David Rock, director of the Neuro-Leadership Institute in New York City, who says diverse coworkers "challenge their own and others' thinking."2 According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), organizational diversity now includes more than just racial, gender, and religious differences. It also encompasses different thinking styles and personality types, as well as other factors such as physical and cognitive abilities and sexual orientation, all of which influence the way people perceive the world. "Finding the right mix of individuals to work on teams, and creating the conditions in which they can excel, are key business goals for today's leaders, given that collaboration has become a paradigm of the twenty-first century workplace," according to an SHRM article.3

Attracting workers who are not all alike is an important first step in the process of achieving greater diversity. However, managers cannot stop there. Their goals must also encompass inclusion, or the engagement of all employees in the corporate culture. "The far bigger challenge is how people interact with each other once they're on the job," says Howard J. Ross, founder and chief learning officer at Cook Ross, a consulting firm specializing in diversity. "Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance. Diversity is about the ingredients, the mix of people and perspectives. Inclusion is about the container璽he place that allows employees to feel they belong, to feel both accepted and different."4

Workplace diversity is not a new policy idea; its origins date back to at least the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA) or before. Census figures show that women made up less than 29 percent of the civilian workforce when Congress passed Title VII of the CRA prohibiting workplace discrimination. After passage of the law, gender diversity in the workplace expanded significantly. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the percentage of women in the labor force increased from 48 percent in 1977 to a peak of 60 percent in 1999. Over the last five years, the percentage has held relatively steady at 57 percent. Over the past forty years, the total number of women in the labor force has risen from 41 million in 1977 to 71 million in 2017.5 The BLS projects that the number of women in the U.S. labor force will reach 92 million in 2050 (an increase that far outstrips population growth).

The statistical data show a similar trend for African American, Asian American, and Hispanic workers (Figure 8.2). Just before passage of the CRA in 1964, the percentages of minorities in the official on-the-books workforce were relatively small compared with their representation in the total population. In 1966, Asians accounted for just 0.5 percent of private-sector employment, with Hispanics at 2.5 percent and African Americans at 8.2 percent. 6 However, Hispanic employment numbers have significantly increased since the CRA became law; they are expected to more than double from 15 percent in 2010 to 30 percent of the labor force in 2050. Similarly, Asian Americans are projected to increase their share from 5 to 8 percent between 2010 and 2050.

Figure 8.2

There is a distinct contrast in workforce demographics between 2010 and projected numbers for 2050. (credit: attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license) Much more progress remains to be made, however.

For example, many people think of the technology sector as the workplace of open-minded millennials. Yet Google, as one example of a large and successful company, revealed in its latest diversity statistics that its progress toward a more

inclusive workforce may be steady but it is very slow. Men still account for the great majority of employees at the corporation; only about 30 percent are women, and women fill fewer than 20 percent of Google's technical roles (Figure 8.3).

The company has shown a similar lack of gender diversity in leadership roles, where women hold fewer than 25 percent of positions. Despite modest progress, an ocean-sized gap remains to be narrowed. When it comes to ethnicity,

approximately 56 percent of Google employees are white. About 35 percent are Asian, 3.5 percent are Latino, and 2.4 percent are black, and of the company's management and leadership roles, 68 percent are held by whites.

Figure 8.3

Google is emblematic of the technology sector, and this graphic shows just how far from equality and diversity the industry remains. (credit: attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Google is not alone in coming up short on diversity. Recruiting and hiring a diverse workforce has been a challenge for most major technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, and Yahoo (now owned by Verizon); all have reported gender and ethnic shortfalls in their workforces.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has made available 2014 data comparing the participation of women and minorities in the high-technology sector with their participation in U.S. private-sector employment overall, and the results show the technology sector still lags.8 Compared with all private-sector industries, the high-technology industry employs a larger share of whites (68.5%), Asian Americans (14%), and men (64%), and a smaller share of African Americans (7.4%), Latinos (8%), and women (36%). Whites also represent a much higher share of those in the executive category (83.3%), whereas other groups hold a significantly lower share, including African Americans (2%), Latinos (3.1%), and Asian Americans (10.6%). In addition, and perhaps not surprisingly, 80 percent of executives are men and only 20 percent are women. This compares negatively with all other private-sector industries, in which 70 percent of executives are men and 30 percent women.

Technology companies are generally not trying to hide the problem. Many have been publicly releasing diversity statistics since 2014, and they have been vocal about their intentions to close diversity gaps. More than thirty technology companies, including Intel, Spotify, Lyft, Airbnb, and Pinterest, each signed a written pledge to increase workforce diversity and inclusion, and Google pledged to spend more than $100 million to address diversity issues.9

Diversity and inclusion are positive steps for business organizations, and despite their sometimes slow pace, the majority are moving in the right direction. Diversity strengthens the company's internal relationships with employees and improves employee morale, as well as its external relationships with customer groups. Communication, a core value of most successful businesses, becomes more effective with a diverse workforce. Performance improves for multiple reasons, not the least of which is that acknowledging diversity and respecting differences is the ethical thing to do.

Which two of these reasons best explain why the author includes the statistics and numbers in the text?

1. The author is trying to appeal to the audience's logical side by supplying numbers and statistics that cannot be argued with to prove the point that diversity in the workplace is still lacking, despite some progress over the years.

2. The author is trying to appeal to the audience's emotions by giving them the stark reality in shocking numbers of how few women and minorities are working in high-level positions or certain types of companies.

3. The author is trying to convince the audience that he's not making this problem up; he's done his research and can speak with authority on this subject.

4. The author is trying to explain why there are disparities in the number of women and minorities in different professions.

A. 1 and 4

B. 1 and 3

C. 2 and 4

D. 2 and 3

-

Question 183:

Read the story attached.

"Roughing It" by Mark Twain

My brother had just been appointed Secretary of Nevada Territory ?an office of such majesty that it concentrated in itself the duties and dignities of Treasurer, Comptroller, Secretary of State, and Acting Governor in the Governor's absence. A salary of eighteen hundred dollars a year and the title of "Mr. Secretary," gave to the great position an air of wild and imposing grandeur. I was young and ignorant, and I envied my brother. I coveted his distinction and his financial splendor, but particularly and especially the long, strange journey he was going to make, and the curious new world he was going to explore. He was going to travel! I never had been away from home, and that word "travel" had a seductive charm for me. Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside. And by and by he would become very rich, and return home by sea, and be able to talk as calmly about San Francisco and the ocean, and "the isthmus" as if it was nothing of any consequence to have seen those marvels face to face.

What I suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe. And so, when he offered me, in cold blood, the sublime position of private secretary under him, it appeared to me that the heavens and the earth passed away, and the firmament was rolled together as a scroll! I had nothing more to desire. My contentment was complete.

At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago ?not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months璉 had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years! I dreamed all night about Indians, deserts, and silver bars, and in due time, next day, we took shipping at the St. Louis wharf on board a steamboat bound up the Missouri River. We were six days going from St. Louis to "St. Jo." ?a trip that was so dull, and sleepy, and eventless that it has left no more impression on my memory than if its duration had been six minutes instead of that many days. No record is left in my mind, now, concerning it, but a confused jumble of savage-looking snags, which we deliberately walked over with one wheel or the other; and of reefs which we butted and butted, and then retired from and climbed over in some softer place; and of sand-bars which we roosted on occasionally, and rested, and then got out our crutches and sparred over.

In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo. by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so.

What is most likely the author's intent in mentioning the difficult time when traveling from St. Louis to "St. Jo"?

A. to show he now regrets accepting the offer to travel with his brother to Nevada Territory

B. to show that riverboat captains were often unprepared for the hidden dangers in the rivers they navigated, which meant there were unnecessary delays

C. to show the difficulty and drudgery of traveling in those days, which is juxtaposed against the excitement and anticipation he felt about the opportunity to travel earlier on in the passage

D. to show how much railways eased the travel burden (Whereas the boat he traveled on kept getting caught on the sandbars and river bottom, making progress slow, a railroad would have sped up the trip immensely.)

-

Question 184:

Read the story attached.

"Roughing It" by Mark Twain My brother had just been appointed Secretary of Nevada Territory ?an office of such majesty that it concentrated in itself the duties and dignities of Treasurer, Comptroller, Secretary of State, and Acting Governor in the Governor's absence. A salary of eighteen hundred dollars a year and the title of "Mr. Secretary," gave to the great position an air of wild and imposing grandeur. I was young and ignorant, and I envied my brother. I coveted his distinction and his financial splendor, but particularly and especially the long, strange journey he was going to make, and the curious new world he was going to explore. He was going to travel! I never had been away from home, and that word "travel" had a seductive charm for me. Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside. And by and by he would become very rich, and return home by sea, and be able to talk as calmly about San Francisco and the ocean, and "the isthmus" as if it was nothing of any consequence to have seen those marvels face to face.

What I suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe. And so, when he offered me, in cold blood, the sublime position of private secretary under him, it appeared to me that the heavens and the earth passed away, and the firmament was rolled together as a scroll! I had nothing more to desire. My contentment was complete.

At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago ?not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months ?I had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years! I dreamed all night about Indians, deserts, and silver bars, and in due time, next day, we took shipping at the St. Louis wharf on board a steamboat bound up the Missouri River. We were six days going from St. Louis to "St. Jo."?a trip that was so dull, and sleepy, and eventless that it has left no more impression on my memory than if its duration had been six minutes instead of that many days. No record is left in my mind, now, concerning it, but a confused jumble of savage-looking snags, which we deliberately walked over with one wheel or the other; and of reefs which we butted and butted, and then retired from and climbed over in some softer place; and of sand-bars which we roosted on occasionally, and rested, and then got out our crutches and sparred over.

In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo. by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so.

You are asked to describe the trustworthiness and reliability of the narrator of the attached passage. Which of these would be the best response?

A. The narrator is not trustworthy because he is too concerned about what he might be missing out on because he says, "I never had been away from home, and that word `travel' had a seductive charm for me." He'll be too busy being jealous that he's only a secretary and not selected to as high a position as his brother to accurately relate the events that will unfold. Jealousy between brothers can run deep and will skew the narrator's perspective as he recounts the events, so he will not be trustworthy.

B. The narrator is trustworthy because he admits to being both excited for his brother and jealous of the opportunity. He admits that what he "suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe" and then when he is offered the opportunity to join his brother, his "contentment was complete" and he hurriedly packed his bags in preparation for departure. This honesty shows we can trust the narrator.

C. The narrator is not trustworthy because he clearly does not like his brother and is looking forward to him possibly being "hanged or scalped." This means that we can't trust his telling of the events because he will always have a negative slant toward his brother. He secretly wants him dead.

D. The narrator is trustworthy because he was there on the trip, too, after his brother invited him to go along as his "private secretary." Because he is so elated to go on this journey, we can trust that he will tell things exactly as they happened and we can trust his account.

-

Question 185:

Read the story attached.

"Roughing It" by Mark Twain

My brother had just been appointed Secretary of Nevada Territory ?an office of such majesty that it concentrated in itself the duties and dignities of Treasurer, Comptroller, Secretary of State, and Acting Governor in the Governor's absence. A salary of eighteen hundred dollars a year and the title of "Mr. Secretary," gave to the great position an air of wild and imposing grandeur. I was young and ignorant, and I envied my brother. I coveted his distinction and his financial splendor, but particularly and especially the long, strange journey he was going to make, and the curious new world he was going to explore. He was going to travel! I never had been away from home, and that word "travel" had a seductive charm for me. Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside. And by and by he would become very rich, and return home by sea, and be able to talk as calmly about San Francisco and the ocean, and "the isthmus" as if it was nothing of any consequence to have seen those marvels face to face.

What I suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe. And so, when he offered me, in cold blood, the sublime position of private secretary under him, it appeared to me that the heavens and the earth passed away, and the firmament was rolled together as a scroll! I had nothing more to desire. My contentment was complete.

At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago ?not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months ?I had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years! I dreamed all night about Indians, deserts, and silver bars, and in due time, next day, we took shipping at the St. Louis wharf on board a steamboat bound up the Missouri River. We were six days going from St. Louis to "St. Jo." ?a trip that was so dull, and sleepy, and eventless that it has left no more impression on my memory than if its duration had been six minutes instead of that many days. No record is left in my mind, now, concerning it, but a confused jumble of savage-looking snags, which we deliberately walked over with one wheel or the other; and of reefs which we butted and butted, and then retired from and climbed over in some softer place; and of sand-bars which we roosted on occasionally, and rested, and then got out our crutches and sparred over.

In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo. by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so.

Reread this passage from the attached text. "Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside." This passage best illustrates the author's use of ____.

A. oxymoron

B. imagery

C. hyperbole

D. metaphor

-

Question 186:

Read the story attached.

"Roughing It" by Mark Twain

My brother had just been appointed Secretary of Nevada Territory ?an office of such majesty that it concentrated in itself the duties and dignities of Treasurer, Comptroller, Secretary of State, and Acting Governor in the Governor's absence. A salary of eighteen hundred dollars a year and the title of "Mr. Secretary," gave to the great position an air of wild and imposing grandeur. I was young and ignorant, and I envied my brother. I coveted his distinction and his financial splendor, but particularly and especially the long, strange journey he was going to make, and the curious new world he was going to explore. He was going to travel! I never had been away from home, and that word "travel" had a seductive charm for me. Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside. And by and by he would become very rich, and return home by sea, and be able to talk as calmly about San Francisco and the ocean, and "the isthmus" as if it was nothing of any consequence to have seen those marvels face to face.

What I suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe. And so, when he offered me, in cold blood, the sublime position of private secretary under him, it appeared to me that the heavens and the earth passed away, and the firmament was rolled together as a scroll! I had nothing more to desire. My contentment was complete.

At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago ?not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months ?I had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years! I dreamed all night about Indians, deserts, and silver bars, and in due time, next day, we took shipping at the St. Louis wharf on board a steamboat bound up the Missouri River. We were six days going from St. Louis to "St. Jo." ?a trip that was so dull, and sleepy, and eventless that it has left no more impression on my memory than if its duration had been six minutes instead of that many days. No record is left in my mind, now, concerning it, but a confused jumble of savage-looking snags, which we deliberately walked over with one wheel or the other; and of reefs which we butted and butted, and then retired from and climbed over in some softer place; and of sand-bars which we roosted on occasionally, and rested, and then got out our crutches and sparred over.

In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo. by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so.

Reread the last paragraph of the attached passage (reproduced here). "In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain had said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so." Which literary device does the narrator use in this paragraph?

A. symbolism of the reefs and snags being obstacles in life to overcome

B. euphemism with the description of "climbing over reefs" rather than "scraping along the bottom"

C. alliteration with the "bully" boat description

D. personification of the boat as a "she"

-

Question 187:

Read the story attached.

"Roughing It" by Mark Twain

My brother had just been appointed Secretary of Nevada Territory ?an office of such majesty that it concentrated in itself the duties and dignities of Treasurer, Comptroller, Secretary of State, and Acting Governor in the Governor's absence. A salary of eighteen hundred dollars a year and the title of "Mr. Secretary," gave to the great position an air of wild and imposing grandeur. I was young and ignorant, and I envied my brother. I coveted his distinction and his financial splendor, but particularly and especially the long, strange journey he was going to make, and the curious new world he was going to explore. He was going to travel! I never had been away from home, and that word "travel" had a seductive charm for me. Pretty soon he would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away on the great plains and deserts, and among the mountains of the Far West, and would see buffaloes and Indians, and prairie dogs, and antelopes, and have all kinds of adventures, and may be get hanged or scalped, and have ever such a fine time, and write home and tell us all about it, and be a hero. And he would see the gold mines and the silver mines, and maybe go about of an afternoon when his work was done, and pick up two or three pailfuls of shining slugs, and nuggets of gold and silver on the hillside. And by and by he would become very rich, and return home by sea, and be able to talk as calmly about San Francisco and the ocean, and "the isthmus" as if it was nothing of any consequence to have seen those marvels face to face.

What I suffered in contemplating his happiness, pen cannot describe. And so, when he offered me, in cold blood, the sublime position of private secretary under him, it appeared to me that the heavens and the earth passed away, and the firmament was rolled together as a scroll! I had nothing more to desire. My contentment was complete.

At the end of an hour or two I was ready for the journey. Not much packing up was necessary, because we were going in the overland stage from the Missouri frontier to Nevada, and passengers were only allowed a small quantity of baggage apiece. There was no Pacific railroad in those fine times of ten or twelve years ago ?not a single rail of it. I only proposed to stay in Nevada three months ?I had no thought of staying longer than that. I meant to see all I could that was new and strange, and then hurry home to business. I little thought that I would not see the end of that three-month pleasure excursion for six or seven uncommonly long years! I dreamed all night about Indians, deserts, and silver bars, and in due time, next day, we took shipping at the St. Louis wharf on board a steamboat bound up the Missouri River. We were six days going from St. Louis to "St. Jo." ?a trip that was so dull, and sleepy, and eventless that it has left no more impression on my memory than if its duration had been six minutes instead of that many days. No record is left in my mind, now, concerning it, but a confused jumble of savage-looking snags, which we deliberately walked over with one wheel or the other; and of reefs which we butted and butted, and then retired from and climbed over in some softer place; and of sand-bars which we roosted on occasionally, and rested, and then got out our crutches and sparred over.

In fact, the boat might almost as well have gone to St. Jo. by land, for she was walking most of the time, anyhow ?climbing over reefs and clambering over snags patiently and laboriously all day long. The captain said she was a "bully" boat, and all she wanted was more "shear" and a bigger wheel. I thought she wanted a pair of stilts, but I had the deep sagacity not to say so.

The narrator of the attached story experiences a variety of feelings about his brother's appointment to serve as Secretary of Nevada Territory. Among the emotions he describes are these three.

A. joy, pity, and disgust

B. concern, anger, and elation

C. uneasiness, surprise, and hostility

D. envy, jealousy, and excitement

-

Question 188:

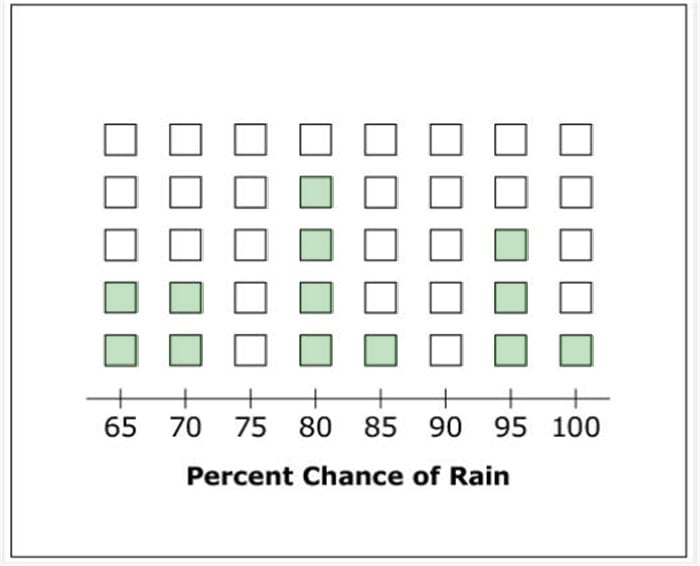

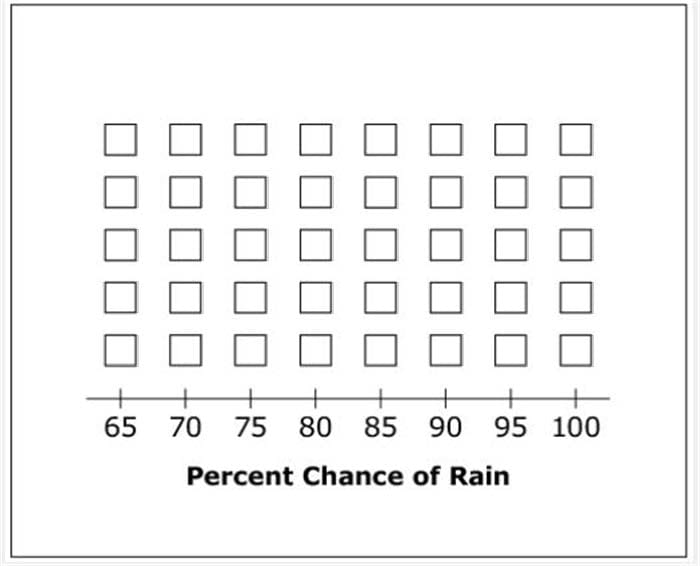

HOTSPOT Click above the numbers to create a line plot for the given percent chances of rain in different cities. 65, 65, 70, 70, 80, 80, 80, 80, 85, 95, 95, 95,100

Hot Area:

-

Question 189:

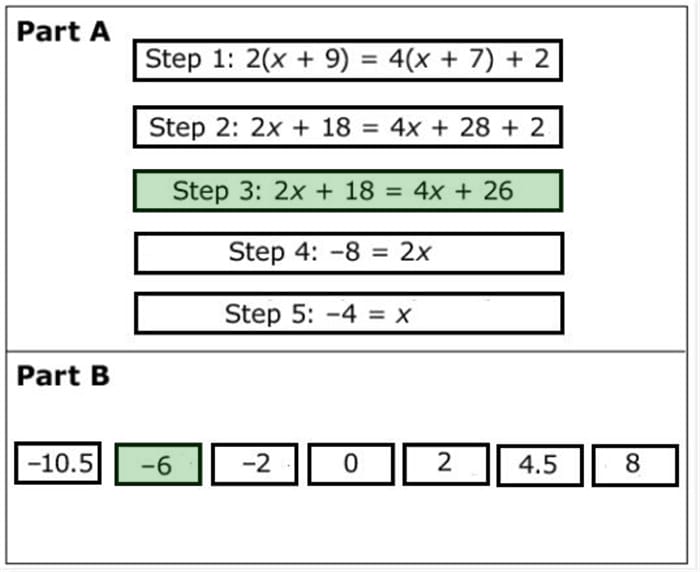

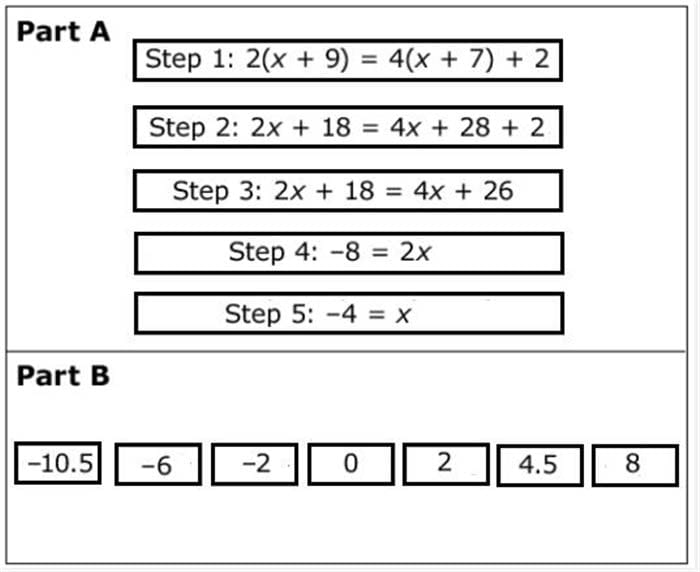

HOTSPOT Emily is solving the equation 2(x + 9) = 4(x + 7) + 2. Her steps are shown below. Part A

Click on the first step in which Emily made an error.

Part B

Click on the solution to Emily's original equation.

Hot Area:

-

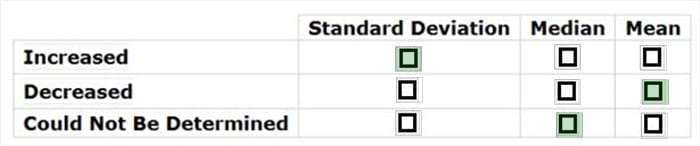

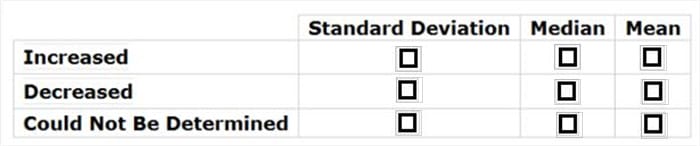

Question 190:

HOTSPOT

Michael took 12 tests in his math class. His lowest test score was 78. His highest test score was 98. On the 13th test, he earned a 64. Choose whether the value of each statistic for his test scores increased, decreased, or could not be determined when the last test score was added.

Hot Area:

Related Exams:

AACD

American Academy of Cosmetic DentistryACLS

Advanced Cardiac Life SupportASSET

ASSET Short Placement Tests Developed by ACTASSET-TEST

ASSET Short Placement Tests Developed by ACTBUSINESS-ENVIRONMENT-AND-CONCEPTS

Certified Public Accountant (Business Environment amd Concepts)CBEST-SECTION-1

California Basic Educational Skills Test - MathCBEST-SECTION-2

California Basic Educational Skills Test - ReadingCCE-CCC

Certified Cost Consultant / Cost Engineer (AACE International)CGFM

Certified Government Financial ManagerCGFNS

Commission on Graduates of Foreign Nursing Schools

Tips on How to Prepare for the Exams

Nowadays, the certification exams become more and more important and required by more and more enterprises when applying for a job. But how to prepare for the exam effectively? How to prepare for the exam in a short time with less efforts? How to get a ideal result and how to find the most reliable resources? Here on Vcedump.com, you will find all the answers. Vcedump.com provide not only Test Prep exam questions, answers and explanations but also complete assistance on your exam preparation and certification application. If you are confused on your SBAC exam preparations and Test Prep certification application, do not hesitate to visit our Vcedump.com to find your solutions here.